To change behaviour, change the environment

To make behaviour change sustainable, take a design approach. This applies equally well to both our personal lives and to our work organisations.

Willpower is for jocks. A limited resource to begin with, made even less useful by being depleted by simple decisions, like what to wear to work or eat for lunch. Constantly switching between tasks seems to be a good way to expend it as well. So relying on willpower to change your (or someone else’s) behaviour is not a sustainable strategy.

But what if you changed the environment instead?

Trying to cut back on candy and snacks? Clear out the cupboards. It’s much easier to avoid foods that take some trouble to obtain. If you need to go to the local store every time to satisfy a craving, it’s less likely that you’ll actually do it.

Trying to start exercising in the morning? Aim for 10 minutes to make the goal easy to achieve and to build positive reinforcement. Then put your sneakers and sportswear next to the bed before going to sleep.

When I finally realised that checking Facebook was likely to put me in a bad mood, I deleted the app. And the apps you want to spend less time on, but don’t want to get rid off completely? Put them in other screens and into folders. The more clicks it takes, the less likely it is you’re going to open them accidentally and without intent.

Want to watch less TV and read more? Leave the remote to another room. And when you finally come home from work and collapse on the couch, have a book waiting at arms reach.

Changing the environment is also the smart and sustainable way to create organisational change. Design processes, metrics, rewards, incentives, information flows, tools, management systems, goal setting, performance reviews etc. in a way that they support the behaviours you want to see from the people in your organisation, and discourage those that are toxic.

Want to be more innovative? Get rid of metrics that encourage people to protect business as usual. Replace them with ones that reward creativity, controlled risk-taking and learning. Get rid of informational silos and start using systems that support total transparency.

And treat those changes as experiments. Organisations are complex adaptive systems, where seemingly simple changes can have surprising and significant side effects. Just look at what happened in Yahoo: Fixed project-based employee evaluations meant that none of the top engineers wanted to work with each other, as it would have reflected poorly on their individual performance scores. Consequently the most important projects never had the best possible team working on them.

Of course, none of this matters if you don't first figure out what the desired personal and organisational behaviours are.

Further reading:

Heath, Chip & Heath, Dan (2010). Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard. New York: Random House.

McChrystal, Stanley et al. (2015). Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Adaptiveness is the new efficiency

In the modern business environment, characterised by increasing complexity, chasing efficiency is quickly becoming a fool's game. Efficiency is inevitably at odds with the organisation's adaptive capability. The time, energy, and effort that optimisation takes has diminishing returns on investment. And in fast-moving industries many optimisation efforts may already be too late upon arrival.

This article was published originally in Quality Intelligence Hub in February 2015. It is now presented here with minor changes and corrections.

Recently my Twitter feed and the blogs I follow have featured an unusually large amount of articles on artificial intelligence. According to the author Sam Harris, the often-stated goal of AI research is to create human-level intelligence. However, he points out that it is a false goal. The computers we use today already possess superhuman capabilities of e.g. computation and storage of information, and that "any future artificial general intelligence (AGI) will exceed human performance on every task for which it is considered a source of ‘intelligence’ in the first place.”

This is a rather powerful vision. Considering how quickly the ability of computer programs to understand natural language has progressed (see, for example, IBM’s Watson), and how digital assistants such as Siri, Google Now, and Microsoft’s Cortana already possess believable communication capabilities, a future depicted in the movie Her, where we communicate verbally with an actual AI, suddenly seems a lot closer.

It would be easy to dismiss this as overoptimistic technophilia, but the fact is that the history of technological advancement progresses in a non-linear fashion. Our entire way of life has changed radically since the industrial revolution some 250 years ago, but within that time frame you can also identify many smaller periods of significant advancements. A pattern emerges. The time frames have consistently become shorter.

Consider how technology has affected our lives in the past five years, then past 10, 20, 50, or 100 years. In order to predict the next 10 years we cannot look at the past 10 and draw a straight line. Every consequent year in the future will see more rapid advancement than the year that came before it.

Are there limits to this? Possibly, but there are also hints of technologies – such as AI – that may result in larger leaps that impact practically everything that comes after. The Internet of Things is an example of such emergence taking place at this very moment. Just consider all the aspects of everyday life that have become affected by the Internet in two short decades, or the fact that the horse remained state-of-the-art in human mobility for thousands of years before the invention of the automobile.

The flipside of efficiency is lost adaptive capability

The challenge this presents to organisations is one rooted in their past. If you look at the history of management practice, you can see it has largely been a race towards efficiency, although the methods and language have changed over the years. The problem with efficiency, however, is that it can only be pursued successfully in a relatively stable environment. Otherwise you risk becoming efficient in doing things that have already become outdated. (1)

When you try to optimise a system, it means reducing variance in the operating parameters of that system. Where an established organisation has found an efficient way to produce certain goods or services for its customers, it has also become restricted by the way those goods and services are being produced. The more specialised and efficient a production line is, the more difficult and expensive it tends to be to reconfigure it – beyond the accepted level of variance that is. Each McDonald’s restaurant needs to follow McDonald’s operations manual, and changing it is not a trifle matter.

This is what allows start-ups to challenge industry giants. As the business environment changes, what used to be an optimised system in the previous environment may no longer be very well optimised at all. A new performance peak has emerged, and an agile, quick-learning start-up is often in a better position to discover and exploit that peak. Think of Kodak, which actually pioneered digital sensors for cameras but was so caught up in its own organisation, trapped in the beast of its own design, that its attempts at creating new kind of organisational alignment, better suited to a digital world, never succeeded. (2)

Efficiency, while it does work in a stable environment, comes with reduced ability to adapt to changes – be they internally induced or originating from outside the organisation. And because business environments are changing faster than ever, trying to optimise for efficiency is becoming a fool’s game. The time, energy, and effort that optimisation takes has diminishing returns on investment. And in fast-moving industries many optimisation efforts may already be too late upon arrival.

A new model of organisation

However, I do believe that organisations can be designed in such manner that they can capture the best of both worlds. The key idea is to recognise which areas are changing faster than others, requiring more adaptive capability, and which ones are relatively stable and can therefore benefit from traditional performance improvement measures. For example, tax accounting tends to be an area that is highly structured, and where optimisation and eliminating variance are something to be desired. On the opposite there are areas that constantly need to reinvent themselves, such as product and service innovation.

In many of the in-between areas there are usually specific things that might benefit from more rigid structures and processes, but also multiple aspects where overenthusiastic top-down control results in nothing but loss of adaptive capability and ability for self-renewal.

Another rule of thumb to keep in mind is Pareto’s 20/80 principle, or that 20% of effort tends to account for 80% of the results, and each subsequent percentage of performance improvement becomes more and more costly to achieve. The principle can also be inverted: 80% of the adaptive capability of a system is lost in order to achieve that final 20% increase in performance. Extrapolated further it can also mean that 64% of the total effort (80% of 80%) goes to achieving the final 4% (20% of 20%) increase in efficiency, and vice versa in the lost adaptive capability.

When seen from this perspective, the role of managers and leaders changes. They need to become architects and designers who build structures and conditions that steer their organisations in the right direction, but are at the same time loose and flexible enough to allow for bottom-up, self-organised, goal-oriented activity to emerge. And in self-organisation lies the key for achieving adaptability and innovativeness, while staying true to the organisation’s business goals.

For a deeper dive into the topic, I would suggest the books Competing on the Edge by Shona Brown and Kathleen Eisenhardt, and Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

References:

1) Kiechel, Walter III (2012). The Management Century. Harvard Business Review, November 2012, 63-75.

2) Lucas Jr, Henry C., & Goh, Jie Mein (2009). Disruptive technology: How Kodak missed the digital photography revolution. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 18, 46-55.

Newton's ghost and management science

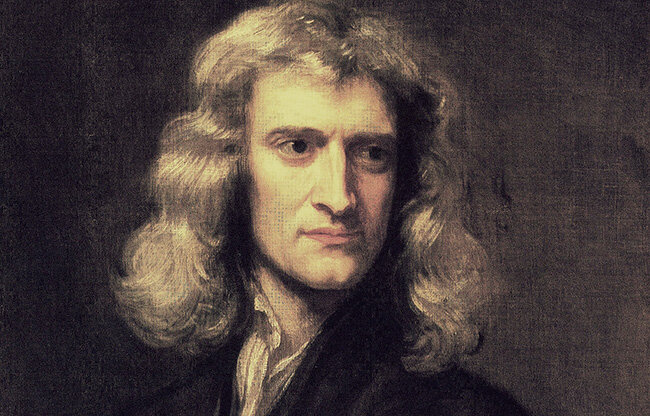

Last week I read an interesting journal article on how the scientific revolution started by Isaac Newton was not just constrained in the scientific domain, but became a cultural revolution as well. What started with Newton in the 17th century–the belief that the mysteries of the natural world can be conquered by rationality and reasoning–has guided much of human endeavours ever since, and continues to influence our lives even today.

By unraveling the mysteries of the universe, Newton became a shining example of our thinking prowess. With his work on the natural laws governing the universe, our culture adopted the idea that we have the brainpower to eventually understand all of nature. And soon it was not just the natural domain, but social sciences as well became enthralled by the Newtonian paradigm: that we can understand society and human behaviour by using a Newtonian, reductionist approach.

Eventually Albert Einstein and others demonstrated that Newton's mechanics fail in the realm of subatomic particles. He did not refute Newton's work, but rather complemented it. Complexity theory should be seen in a similar manner. It does not refute the validity of reductionist and deterministic approaches in the context of non-complex systems. But like Newton's mechanics not being able to explain the behaviour of subatomic particles, we should acknowledge that complex systems present a context where the reductionist and deterministic approaches are bound to fail.

This is a paradigm shift that is slowly taking place. Yet when talking about human organisations and institutions, its impact has not really even started to show itself. The few companies (e.g. W.L. Gore and Semco come to mind) that seem to have intrinsic understanding of complexity, and how to take advantage of it, are seen as oddballs and exceptions. That is because you cannot simply copy what Gore or Semco are doing and expect it to work in your organisation, but by using complexity principles you can create your own working model.

Being in its infancy, the application of complexity theory–and the complex adaptive systems framework–in organisation design represents a huge opportunity for those who have the courage to move first, and to abandon the century-old model of industrial organisation.

If Gary Hamel claims that "...your company has 21st century, internet-enabled business processes, mid-20th century management processes, all built atop 19th century management principles," what remains unsaid is that those 19th century management principles are grounded on 17th century natural science, and traceable specifically to Isaac Newton and René Descartes.

References:

Louth, Jonathon (2011). From Newton To Newtonianism: Reductionism And The Development Of The Social Sciences. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, Vol. 13, No. 4, 63-83.

The edge of chaos: Where complexity science meets organisational performance

One of the things I particularly like about viewing organisations through the lens of complexity science is that it does not just attempt to describe organisations, but it also prescribes how they should operate in order to maximise performance. There are two key concepts in this: fitness landscapes and the edge of chaos.

Imagine a mountain range with many jagged peaks. Some are perhaps a few hundred meters tall, while others stretch up thousands of meters, reaching high above the clouds. This landscape represents the competitive environment of a specific industry. The individual peaks stand for different ways an organisation can chase performance. The higher the peak, the better the performance. There are three conditions:

A company may occupy only one peak at a time;

The height of the peaks cannot be seen very well when standing on the ground. Instead, one needs to occupy a peak in order to better survey the landscape;

The landscape itself changes. Peaks may rise and fall as time passes.

A fitness landscape? Or perhaps just a regular landscape.

Let's take this metaphor further by using Nokia as an example. When they decided to enter the mobile phone industry, they effectively entered into an entirely new mountainous landscape. And as they were one of the first companies there, it was not possible to see which of the performance peaks one should attempt to climb because no one knew where the highest peaks were. One had to engage in exploration. Nokia did this well, managing to find and scale one of the highest peaks, setting up shop there and becoming the world's largest mobile phone manufacturer.

Gradually they became better and better at exploiting the opportunities found in their performance peak, increasing efficiency and operational excellence. All was well and good until the landscape started changing. The peak they had found and successfully exploited began to fall in the shadow of other peaks, which were discovered and exploited by companies such as Apple and Google.

The more turbulent the industry, the faster the fitness landscape changes. Old performance peaks become obsolete and new ones arise.

This is a story that has repeated itself countless of times across different industries: The established corporations become stagnant, focused on exploiting their current competences and position in the competitive environment, and failing to see that the environment is not anymore the same it was when they became dominant. Or even if they see that change is inevitable, the efforts to resist it tend to be stronger than the efforts to innovate.

They become incapable of dismantling all the structures built for successfully exploiting the performance peak they have settled on. Without this conscious removal of structure and open engagement in a period of exploration it is not possible to find new and more promising peaks. Think, for example, the inability of recording industry to take advantage of digitalisation, or the lackluster response of American car industry to increasing competitive pressures. Established companies have a tendency to become so focused on the position built on a given performance peak that moving to a new one, and learning again how to exploit it, will never take place. Or if it will, it is only in the face of absolute necessity and involving considerable pain.

Startups are another great example. They are unencumbered by existing structures, built to exploit a particular peak in their industry, which means that they are free to explore the landscape to discover new larger peaks. The concept of fitness landscapes also explains why many initially successful startups become vulnerable later in their life: after finding and settling on a newly discovered performance peak, their focus shifts from exploration to exploitation, optimisation and operational excellence, which in turn makes them forget how to scan the landscape for changes and engage in exploration.

It is an easy thing to say that companies need to cultivate the ability to simultaneously exploit performance peaks in their competitive environment, while also engaging in exploration to discover new higher peaks. To actually do it is a different story, and this is where the edge of chaos comes in.

Organisations like other Complex Adaptive Systems perform best when they are at the edge of chaos. It is a place where the organisation has just enough structure to stay cohesive, preventing it from being pulled apart by competing internal and external forces. Emphasis on just enough. Because the openness to chaos, the ability to dismantle existing structures, to change shape rapidly, they all precede the ability to innovate and to explore new performance peaks in the ever-changing competitive environment. As stated by Shona Brown and Kathleen Eisenhardt:

...the edge of chaos lies in an intermediate zone where organisations never quite settle into a stable equilibrium but never quite fall apart, either. This intermediate zone is where systems of all types—biological, physical, economic, and social—are at their most vibrant, surprising, and flexible. The power of a few simple structures to generate enormously complex, adaptive behaviour—whether flock behaviour among birds, resilient government (as in democracy), or simply successful performance by major corporations — is at the heart of the edge of chaos. The edge of chaos captures the complicated, uncontrolled, unpredictable but yet adaptive (in technical terms, self-organised) behaviour that occurs when there is some structure but not very much. The critical managerial issue at the edge of chaos is to figure out what to structure, and as essential, what not to structure.

- Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos (Brown & Eisenhardt, 1998)

To stay at the edge of chaos requires energy and conscious effort. Complex Systems have a natural tendency to swing either to the chaotic (i.e. to fall apart), or the static (to become stagnant, controlled, and bureaucratic). Organisations need to maintain activities that are purposefully designed to disrupt the existing behaviour. Activities such as experimentation, or the continuous effort to test what works and what does not work, resulting in learning, and the discovery of new opportunities and new performance peaks. Another method is time-pacing, or the systemic effort to generate periodic change from within (e.g. 3M's self-imposed rule that each year 30 % of revenues must come from new products, forcing the company to stay innovative).

My personal experience from different organisations is that there typically is way too much structure and way too little openness for chaos. Yes, some structure will be necessary in order to achieve anything, but it quickly becomes a hindrance to the long-term survivability and performance of the organisation. Here are some questions to get you started in figuring out where and how much structure is needed:

How is the competitive environment of the organisation? The more uncertain, complex, and turbulent, the more the organisation needs to lean towards chaos.

What is the organisations business? An organisation dealing with one-time products and services (e.g. creative agencies, consultancies), or innovative new technologies needs to be more open to chaos and exploration than an organisation such as the IRS. In fact, I don't think anyone would enjoy seeing much experimentation and exploration in the way the government handles our taxes...

Where in the organisation is structure needed, and where it isn't? There are certain activities in every organisation that should go according to specification every single time, such as accounting, hiring, firing and others where e.g. laws need to be followed to the letter. Yet it is good to understand what kind of structure is really needed, and what is superfluous. For example, whether or not employees in accounting wear business attire has nothing to do with how well they are able to do their jobs, yet some companies have created a structure that regulates clothing. On the other hand, there are also activities–namely those that require creativity, agility and innovation–that are particularly sensitive to the harm caused by unnecessary structure.

Think broad guidelines instead of specific instructions. Self-organisation is a property of Complex Adaptive Systems, meaning that the system is capable of figuring out on its own how things should be done. In this sense the purpose of Organisation Design is not to provide specific rules for handling different situations, but to provide boundaries that ensure that the self-organising processes (unhindered by unnecessary structure) are aimed in the right direction. These boundaries include, for example, the organisations mission (why the organisation exists), vision (where it is headed), strategy (how it is going to get there), and values (what kind of behaviour it expects). When these are clearly understood by everyone in the organisation, it creates limits to the self-organising behaviour.

As a summary, the more there is structure in an organisation, the worse it tends to be at innovating, reacting to rapid changes in the business environment, discovering new opportunities, and taking advantage of them. Therefore it becomes an absolutely essential question of Organisation Design where, how much, and what kind of structures are needed, and what kind of mechanisms should be used to periodically challenge those structures, so that their value can be re-estimated in the light of the changing environment. For this, complexity science provides a framework, vocabulary, and way of thinking that is a clear departure from the century old model of industrial organisation.

References and further reading:

Brown, S. L., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (1998). Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Carroll, T., & Burton, R. M. (2000). Organizations and Complexity: Searching for the Edge of Chaos. Computational & Mathematical Organization Theory, Vol. 6, Iss. 4, 319-337.

Lansing, Stephen J. (2003). Complex Adaptive Systems. Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 32, 183-204.

March, James G. (1991). Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organization Science, Vol. 2, No. 1, 71-87.

Starbuck, W. H., Barnett, M. L., & Baumard, P. (2008). Payoffs and pitfalls of strategic learning. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 66, Iss. 1, 7-21.

Thinking, systems and performance

Earlier this week I spotted a tweet by Hermanni Hyytiälä from Reaktor and it spurred me to write this article.

It is a wonderfully simple illustration making the point that the systems we build are based on the type of thinking we hold, and these two combined lead to certain outcomes. When it comes to modern day organisations, the 'thinking' part is still firmly founded on the history of mass production, with its origins in the early car industry. This production line view of the world, on the other hand, is very much based on the Newtonian/Cartesian deterministic model.

In plain English, the early scientific revolution and "scientism" got us to think that we can dismantle everything into pieces, and by rigorously studying those individual pieces we can understand and improve the whole. Production line as a management system for organising work is a representation of that thinking. You take a complicated end product, such as a car, and figure out how to accelerate the manufacturing and assembly of each of its parts.

Similar thinking can be seen in organisations as a whole. An organisation is a complex entity, and in order to understand and optimise it we have taken it apart, split it into functions such as HR, Procurement, Marketing, Accounting etc. Add to that different geographies, product lines, customer segments, and the modern-day love affair with cross-functional project work, and you end up with matrixes of so many layers that no one has clear understanding anymore of how the whole thing is supposed to work, who does what, and where.

These types of hierarchies in disguise and command and control organisations (system), based on determinist principles (thinking), perform well when two conditions are met: First, changes in the business environment of the organisation are predictable and take place at a slow pace. Second, the organisation itself is focused on routine, unchanging outputs, which makes optimisation (another term for incremental as opposed to radical innovation) the name of the game. Think of the early Ford motor company with only one product.

We of course know that the first condition is being challenged in almost every single industry. The speed of change has been accelerating for decades. As for the second condition, more and more organisations perform one-of-a-kind services or develop products that are unlike one another. Think of software development, video games, creative agencies, or even consumer electronics companies facing increasing pressure to create something truly innovative.

With these conditions being challenged, we need to think differently about organisations. And if the thinking–or the underlying principles and perceptions–does not change, organisational improvements are akin to tinkering and tweaking, whereas the real issue can be found at the core, at the fundamental principles of organising.

I wholeheartedly believe that the way to design better organisations can be found in complexity science. Seeing organisations as Complex Adaptive Systems gives you a whole different perspective than the traditional deterministic view. Organisations become alive, not static, and that is reflected in the design principles. The role of management changes from control to guidance. People's innate talents have more room to flourish, and barriers to innovate get removed. Command and control does not lose its role entirely, but becomes limited to areas where it makes sense.

This is the much needed change. Complexity theory and its principles, together with the concept of Complex Adaptive Systems (thinking) form the basic foundation for designing better organisations (system).

References and further reading:

Anderson, Philip (1999). Complexity Theory and Organization Science. Organization Science, Vol. 10, No. 3, 216-232.

Brown, S. L., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (1998). Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos. Harvard Business Review Press.

Carlisle, Y., & McMillan, E. (2006). Innovation in organizations from a complex adaptive systems perspective. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2-9.

McMillan, E., & Carlisle, Y. (2007). Strategy as Order Emerging from Chaos: A Public Sector Experience. Long Range Planning, Vol. 40, Iss. 6, 574-593.

Wheatley, Margaret J. (2006). Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World. San Francisco: Berret-Koehler Publishers, 3rd edition.

On designing organisations

As I was doing the literature review for my MSc thesis this summer, reading about uncertainty, I got in my head the idea that I probably should check what has been written about complexity, as those two things seemed related. Little did I know what I was getting myself into. The result was some very exciting ideas and profound changes in my thinking.

Getting myself familiar with articles by various scholars, as well as books such as Margaret Wheatley's Leadership and the New Science and Peter Senge's The Fifth Discipline brought forth the notion of complex adaptive systems, and I think within this concept lies the future of how organisations should be designed in order to thrive in a business environment that is constantly changing. (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Even though the management and design of organisations have evolved from the days of Scientific Management, they are arguably still rooted in the same Newtonian/Cartesian paradigm that makes us see organisations essentially as mechanistic - as opposed to human - systems. A paradigm that assumes that systems can be understood by studying their constituent parts in isolation. This is exemplified in the methods and vocabulary of organisation design; how organisations are largely treated as a collection of functions, jobs, positions, departments, hierarchies, reporting relationships etc. Static pieces of machinery.

Management of organisations, when based on the Newtonian/Cartesian principles, is nothing but an attempt to create order from chaos with the end goal of improving the production of routine outputs. This form of thinking has its roots in the production line and has since crept upon all aspects of organisations. Efficiency is the ultimate goal. Not even innovation management has succeeded in escaping the organisation as a machine. In such a clockwork system stock arrives just-in-time and production can quickly adapt to changes in demand. And anything that can cause a disturbance in that system is seen as a threat that needs to be eliminated. (6)

What is especially disturbing about this belief system - and yes, it is a belief system, nothing more - is that when taken to its logical conclusion the end result is death: A perfect mechanistic organisation has reached the point where all variation is eliminated. It is a machine that happily does what it was set out to do, always in the same way, and always with the same results. And for this to happen the people within that organisation, within that machine, have to become equally invariable parts of it.

Imagine living every day of your (working) life exactly the same way. Same routines in the morning, same tasks performed always in the same way at work, same food for lunch, same activities in the evening after work. After all, we would not want to do anything that causes variance in behaviour and performance the following day. This is not a description of life, but of death. There is movement, like in the blowing of the wind, but that does not mean the wind is alive.

I wonder how many managers can actually identify the core assumptions that lie behind the way their organisations have been designed to operate...

Luckily, however, the reality of the world we live in makes a perfect mechanistic organisation practically impossible. Well, not exactly impossible but inefficient and a poor match to its environment, leading it to be destroyed by selection pressure. Chaos, uncertainty, and unpredictability are essential characteristics of life which ensure that we never reach the state of efficient stagnation that traditional management practice secretly desires. Life itself changes and evolves, and as a result nothing will remain the same. It's just that the speed of change may vary. Many organisations built on mechanistic principles have learned this the hard way. They are either gone or in a state of permanent decline. Entrepreneurship, incidentally, is one of the many forces contributing to the chaos in the business environment, creating selection pressures to established organisations. (7, 8)

What emerges from this line of thinking is a worldview where organisations striving to reach stability - meaning efficient production of routine outputs - will not survive the next big change in the ever-evolving environment. And this brings us back to the concept of complex adaptive systems. Instead of being designed to create order from chaos, organisations need to be designed to thrive in chaos. Not just to withstand or tolerate changes, but to actually become stronger through them. The two perspectives are fundamentally different in how they affect management, business strategy, organisation design, and the process of organising itself. (9, 10)

This is a topic I intend to focus on more carefully in the coming months, in the writings in this blog, as well as in my research. Consider this article as a sort of an introduction, or an invitation, to a journey that aims to challenge some of the very basic assumptions we have about organisations, and to discover ways to make them truly fit for this complex and continuously changing world we live in.

References:

(1) Wheatley, Margaret J. (2006). Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World. San Francisco: Berret-Koehler Publishers, 3rd edition.

(2) Anderson, Philip (1999). Complexity Theory and Organization Science. Organization Science, Vol. 10, No. 3, 216-232.

(3) Senge, Peter M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline (Revised Edition), London: Random House.

(4) Arthur, W. Brian (1999). Complexity and the Economy. Science, Vol. 284, 107-109.

(5) Gell-Mann, Murray (1994). Complex Adaptive Systems. In Cowan, G., Pines, D., & Meltzer, D. (Eds.) Complexity: Metaphors, Models, and Reality, Addison-Wesley. 17-29.

(6) Cooke-Davies, T., Cicmil, S., Crawford, L., & Richardson, K. (2007). We're Not In Kansas Anymore, Toto: Mapping the Strange Landscape of Complexity Theory, and Its Relationship to Project Management. Project Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2, 50-61.

(7) Sarasvathy, Saras D., Dew, N., Read, S., & Wiltbank, R. (2008). Designing Organizations that Design Environments: Lessons from Entrepreneurial Expertise. Organization Studies, 29(03), 331-350.

(8) Sarasvathy, S. D., & Dew, N. (2005). Entrepreneurial logics for a technology of foolishness. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 21, 385-406.

(9) Eisenhardt, K. M., & Brown, S. L. (1998). Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos. Long Range Planning, Vol. 31, No. 5, 786-789.

(10) Drazin, R., & Sandelands, L. (1992). Autogenesis: A Perspective on the Process of Organizing. Organization Science, Vol. 3, No. 2, 230-249.